WEST GERMANIC

Slaap, kindje, slaap

Linguistics

| 14-02-2020

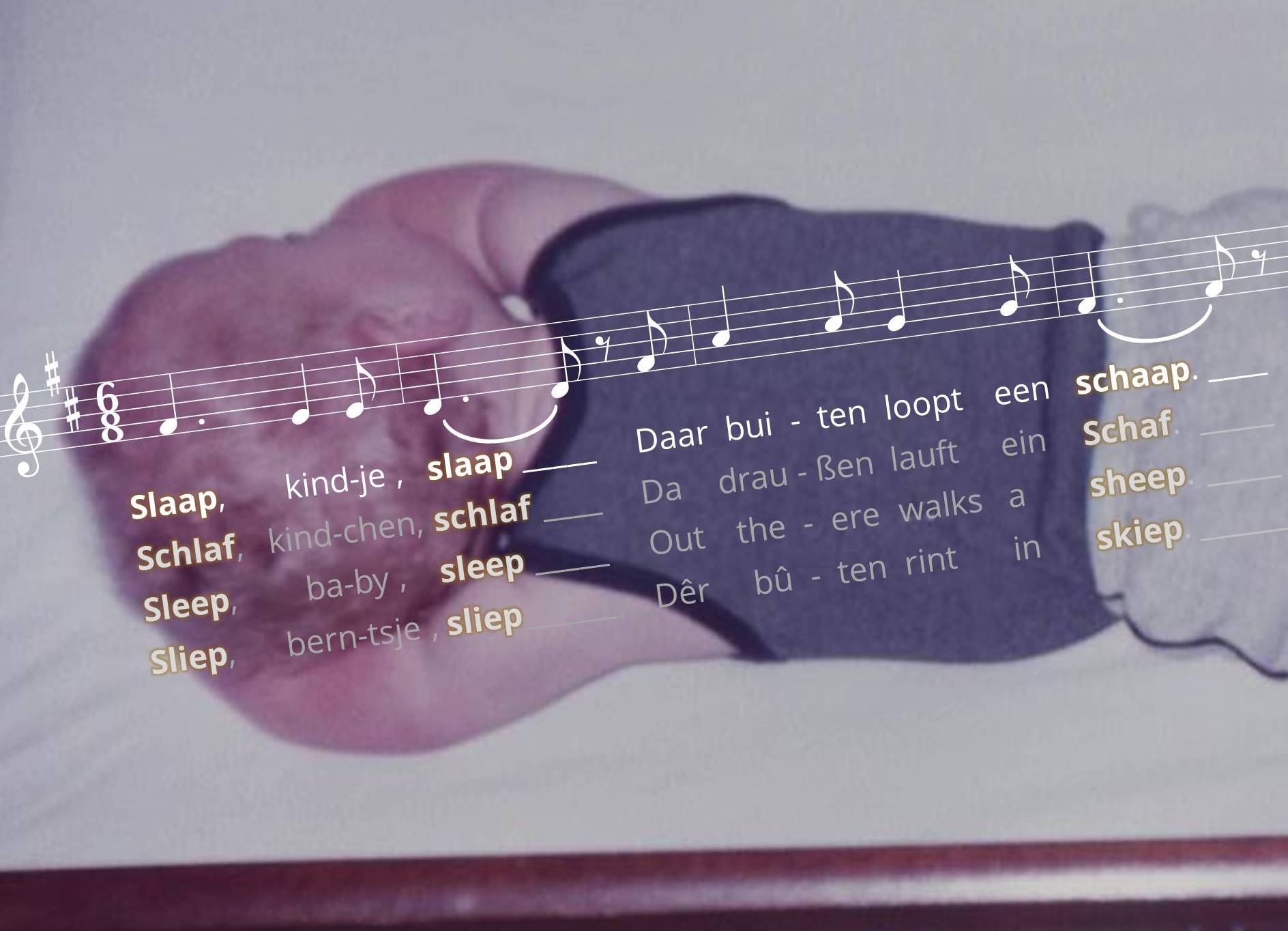

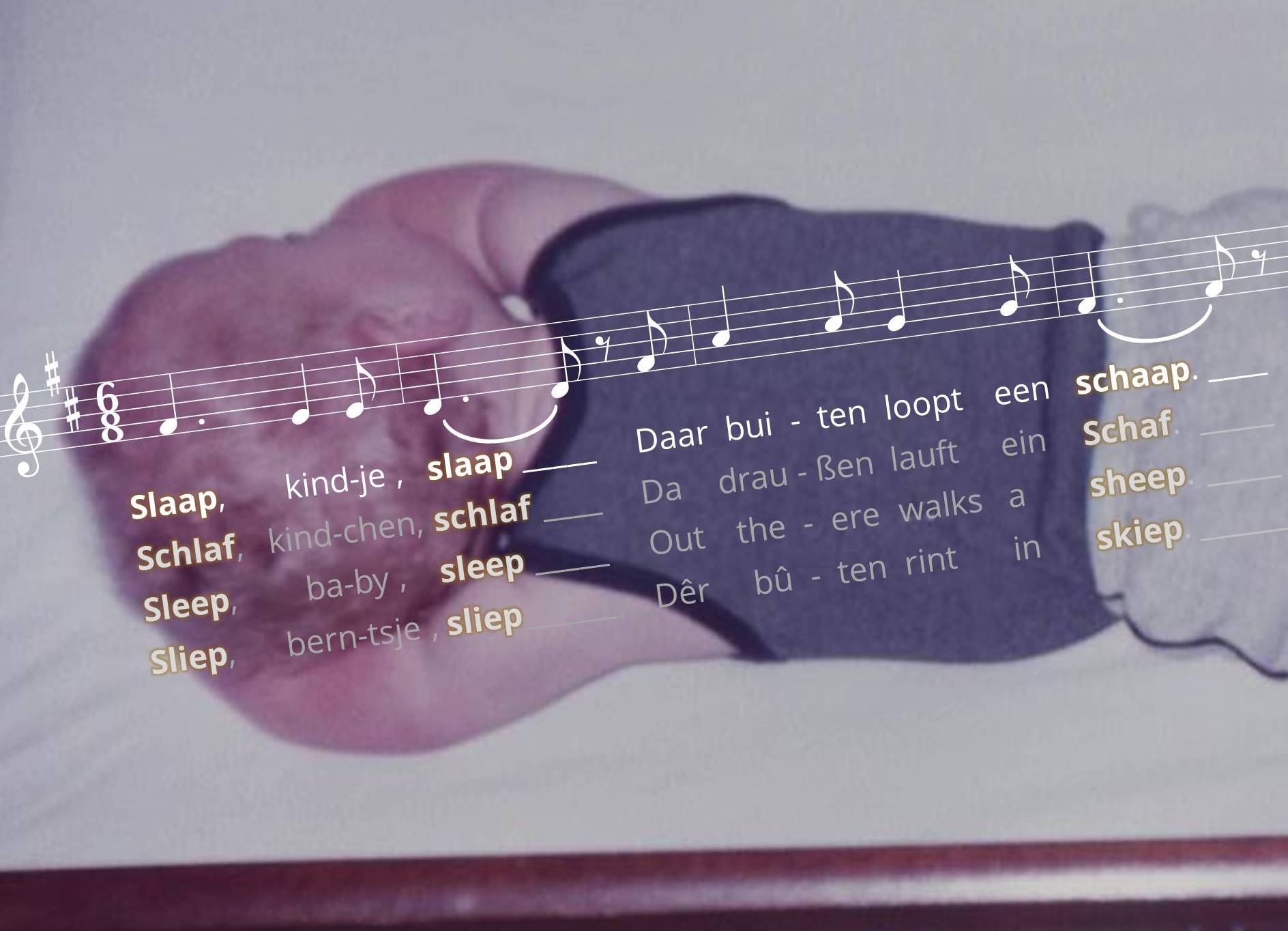

‘Slaap, kindje, slaap / daar buiten loopt een schaap.’ It is a well-known Dutch lullaby, and not immediately high-quality poetry. Yet those two sentences are more interesting than they seem at first sight, especially if you look beyond the Dutch language borders.

For the 'West Germanic' series I translate the words I write about from Dutch into German, English and Frisian. When writing the previous episode, The singular form of sheep, I did that too, and doing so I noticed that Dutch and German both have an [a]-sound in the word for sheep, while Frisian and English both have a long [i]-sound. And while that was running through my mind, I associated the word schaap with slaap because of the aforementioned lullaby, and to my surprise discovered that those words are also rhymes in German, English and Frisian. Let's have a look:

Schlaf, Kindchen, schlaf

Da draußen läuft ein Schaf

Sleep, baby, sleep

Out there walks a sheep

Sliep, berntsje, sliep

Dêr bûten rint in skiep

In the next paragraph I'll come back to the translations used, because I have to make some remarks on that. However, the idea is clear: there's something special going on here. Exactly how special it is that those words rhyme in all four languages, becomes really clear if you look at the other words in the sentences. Whether you look at the translation of kindje, of daar buiten or of loopt, the four languages have very different words for it, although German is closer to Dutch than English, and Frisian is somewhere in between. In my article about sheep I found out that there is no Indo-European tribe for that word. Which naturally raises the question: does that also apply to sleep?

Translations and variations

As I indicated before, I have to make some remarks on the translations I used above. For a start, my point of departure has been that I want to compare words from different languages. That is why I chose berntsje in Frisian, which really means 'little child' like Dutch kindje, although the song is sung in Frisian with popke, which means 'baby' or in Dutch baby'tje. My starting point also produces sentences that doesn't run very well, like Out there walks a sheep, although that's better yet than the very literal translation There outside walks a sheep, which is of course more interesting for comparison at word level. It's is not for nothing that the English version of the lullaby uses other words: Sleep, baby, sleep / Your father tends the sheep. The same applies to the German version: Schlaf, Kindlein, schlaf / Der Vater hüt't die Schaf. In the German version, something else stands out: the various sources I could find contradict each other when it comes to the imperative (Imperativ). On one site it says that it must be Schlafe, but that the last 'e' is not pronounced in practice, which in the song produces Schlaf'. Other sources claim that the imperative in the singular is only the stem of the word. Comparing the different sources, I reckon that in the past the form Schlafe was common, but nowadays the form Schlaf is the norm.

Protogerman lullabies Having made those remarks, we can now go back in time a little further. First let me list the words that the predecessors of German, English, Frisian and Dutch knew for the verb '(to) sleep', according to the classification I also used with sheep:

As you can see, also with '(to) sleep', the distribution is 'long [a]-sound' for the Elbe-Weser-Rhine-Germanic and 'long [i]-sound' for the North Sea Germanic, although the English pronunciation seems a bit closer to an [a]-sound here. Now the comparison with sheep is a bit flawed, because that is a noun and (to) sleep is a verb, but that's easy to solve: from that verb the noun sleep is derived. In the previous episode we saw that the word skēpa was probably used for schaap in Protogerman. And what does it say in the EWN under slapen? “Hierbij ook het zn. pgm. *slēpa- ‘slaap’.” ("With this also the pgm. noun *slēpa- 'sleep'.") It may sound a bit strange, but I really get a bit of a happy feeling when I 'discover' that. I mean, skēpa and slēpa, both with a comparable sound development to a long [a]-sound in German and Dutch and a long [i]-sound in English and Frisian – isn't that something very special? Two words that go back to the same time, centuries ago, that have undergone almost the same development in multiple languages and are still used and still rhyme in four contemporary standard languages. In addition, both schaap as well as slapen and slaap (as well as their German, English and Frisian equals) originate in Protogerman words without an Indo-European ancestor or variant. The EWN says about slēpa: 'The word has replaced an Indo-European word for 'sleeping' in West and East Germanic.' Hypothetically speaking, speakers of Old Dutch, Old Saxon, Old High German, Old Frisian and Old English could have all been able to sing a lullaby in which their word for sleep rhymed with their word for sheep!

Even more resemblance

As if there was not enough beautiful to tell based on two lines from a lullaby with a simple end rhyme, there is even more that stands out. And here too the resemblance between sheep and (to) sleep or sleep applies.

The first is something that only applies to English. Where with 'sheep' the singular and plural are the same word – both sheep – with 'sleeping' the verb is the same as the noun: both sleep. No strong resmblance? Agreed. But it is striking that English is the only one of the four that has lost the second syllable. The other three languages all have a final syllable with a schwa ([ǝ], like the 'a' in about) in their verb for '(to) sleep', while all four languages have lost the 'a' of slēpa in their noun for 'sleep'.

Now, let's have a look at German compared to the other three:

Whereas the words in English, Frisian and Dutch end with a -p, German uses an -f. This is not unique for Schaf and schlafen. Quite the contrary, it is so common that it is seen as part of what is called the High German consonant shift. That is, put very simply (as in: really very simply), the point around the year 600 at which German separated itself from Dutch for a number of sounds (see also the family tree I posted earlier). But they did it so consistently that schlaf and Schaf continued to rhyme. Which is, then again, the beauty of the German gründlichkeit. .

Slaap, kindje, slaap... (Sleep, baby, sleep)

Translatable end rhymeFor the 'West Germanic' series I translate the words I write about from Dutch into German, English and Frisian. When writing the previous episode, The singular form of sheep, I did that too, and doing so I noticed that Dutch and German both have an [a]-sound in the word for sheep, while Frisian and English both have a long [i]-sound. And while that was running through my mind, I associated the word schaap with slaap because of the aforementioned lullaby, and to my surprise discovered that those words are also rhymes in German, English and Frisian. Let's have a look:

Schlaf, Kindchen, schlaf

Da draußen läuft ein Schaf

Sleep, baby, sleep

Out there walks a sheep

Sliep, berntsje, sliep

Dêr bûten rint in skiep

In the next paragraph I'll come back to the translations used, because I have to make some remarks on that. However, the idea is clear: there's something special going on here. Exactly how special it is that those words rhyme in all four languages, becomes really clear if you look at the other words in the sentences. Whether you look at the translation of kindje, of daar buiten or of loopt, the four languages have very different words for it, although German is closer to Dutch than English, and Frisian is somewhere in between. In my article about sheep I found out that there is no Indo-European tribe for that word. Which naturally raises the question: does that also apply to sleep?

Translations and variations

As I indicated before, I have to make some remarks on the translations I used above. For a start, my point of departure has been that I want to compare words from different languages. That is why I chose berntsje in Frisian, which really means 'little child' like Dutch kindje, although the song is sung in Frisian with popke, which means 'baby' or in Dutch baby'tje. My starting point also produces sentences that doesn't run very well, like Out there walks a sheep, although that's better yet than the very literal translation There outside walks a sheep, which is of course more interesting for comparison at word level. It's is not for nothing that the English version of the lullaby uses other words: Sleep, baby, sleep / Your father tends the sheep. The same applies to the German version: Schlaf, Kindlein, schlaf / Der Vater hüt't die Schaf. In the German version, something else stands out: the various sources I could find contradict each other when it comes to the imperative (Imperativ). On one site it says that it must be Schlafe, but that the last 'e' is not pronounced in practice, which in the song produces Schlaf'. Other sources claim that the imperative in the singular is only the stem of the word. Comparing the different sources, I reckon that in the past the form Schlafe was common, but nowadays the form Schlaf is the norm.

Protogerman lullabies Having made those remarks, we can now go back in time a little further. First let me list the words that the predecessors of German, English, Frisian and Dutch knew for the verb '(to) sleep', according to the classification I also used with sheep:

| Elbe-Weser-Rhine-Germanic | North Sea Germanic |

|---|---|

| Old Dutch: slāpan | Old Frisian: slēpa |

| Old Saxon: slāpan | Old English: slæpan |

| Old High German: slāfan |

As you can see, also with '(to) sleep', the distribution is 'long [a]-sound' for the Elbe-Weser-Rhine-Germanic and 'long [i]-sound' for the North Sea Germanic, although the English pronunciation seems a bit closer to an [a]-sound here. Now the comparison with sheep is a bit flawed, because that is a noun and (to) sleep is a verb, but that's easy to solve: from that verb the noun sleep is derived. In the previous episode we saw that the word skēpa was probably used for schaap in Protogerman. And what does it say in the EWN under slapen? “Hierbij ook het zn. pgm. *slēpa- ‘slaap’.” ("With this also the pgm. noun *slēpa- 'sleep'.") It may sound a bit strange, but I really get a bit of a happy feeling when I 'discover' that. I mean, skēpa and slēpa, both with a comparable sound development to a long [a]-sound in German and Dutch and a long [i]-sound in English and Frisian – isn't that something very special? Two words that go back to the same time, centuries ago, that have undergone almost the same development in multiple languages and are still used and still rhyme in four contemporary standard languages. In addition, both schaap as well as slapen and slaap (as well as their German, English and Frisian equals) originate in Protogerman words without an Indo-European ancestor or variant. The EWN says about slēpa: 'The word has replaced an Indo-European word for 'sleeping' in West and East Germanic.' Hypothetically speaking, speakers of Old Dutch, Old Saxon, Old High German, Old Frisian and Old English could have all been able to sing a lullaby in which their word for sleep rhymed with their word for sheep!

Even more resemblance

As if there was not enough beautiful to tell based on two lines from a lullaby with a simple end rhyme, there is even more that stands out. And here too the resemblance between sheep and (to) sleep or sleep applies.

The first is something that only applies to English. Where with 'sheep' the singular and plural are the same word – both sheep – with 'sleeping' the verb is the same as the noun: both sleep. No strong resmblance? Agreed. But it is striking that English is the only one of the four that has lost the second syllable. The other three languages all have a final syllable with a schwa ([ǝ], like the 'a' in about) in their verb for '(to) sleep', while all four languages have lost the 'a' of slēpa in their noun for 'sleep'.

Now, let's have a look at German compared to the other three:

| German | English | Frisian | Dutch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schaf | sheep | skiep | schaap |

| schlafen | (to) sleep | sliepe | slapen |

Whereas the words in English, Frisian and Dutch end with a -p, German uses an -f. This is not unique for Schaf and schlafen. Quite the contrary, it is so common that it is seen as part of what is called the High German consonant shift. That is, put very simply (as in: really very simply), the point around the year 600 at which German separated itself from Dutch for a number of sounds (see also the family tree I posted earlier). But they did it so consistently that schlaf and Schaf continued to rhyme. Which is, then again, the beauty of the German gründlichkeit. .

WEST GERMANIC

In the West Germanic section every other week I discuss a word that strikes me. I look at the meanings and forms of the word, and especially at where the word originates from. With that I compare the four West Germanic languages Dutch, English, Frisian and German, with the occasional inevitable trip across the fictional West Germanic border.

In the next episode: Boter, Brot en griene cheese...

Sources

Most sources are indicated in the text as a link. For German I used the 'Van Dale Study Dictionary' (first edition, 2006).

Image: own photo.