WEST GERMANIC

Knibbel

Linguistics

| 15-03-2021

At the sight of the title of this piece, in the Dutch part of my brain, the phrase "knibbel knabbel knuisje"* comes up, or the word beknibbelen (skimp in English. Beknibbelen is related to knabbelen, which is nibble in English), but that's not what this piece is about. At the sight of the same title, the Frisian part of my brain is suddenly very aware of the feeling in the joints halfway through my legs, and meanwhile translates the word knibbel into knie (knee). Amazing, that brain.

Germanic unanimity

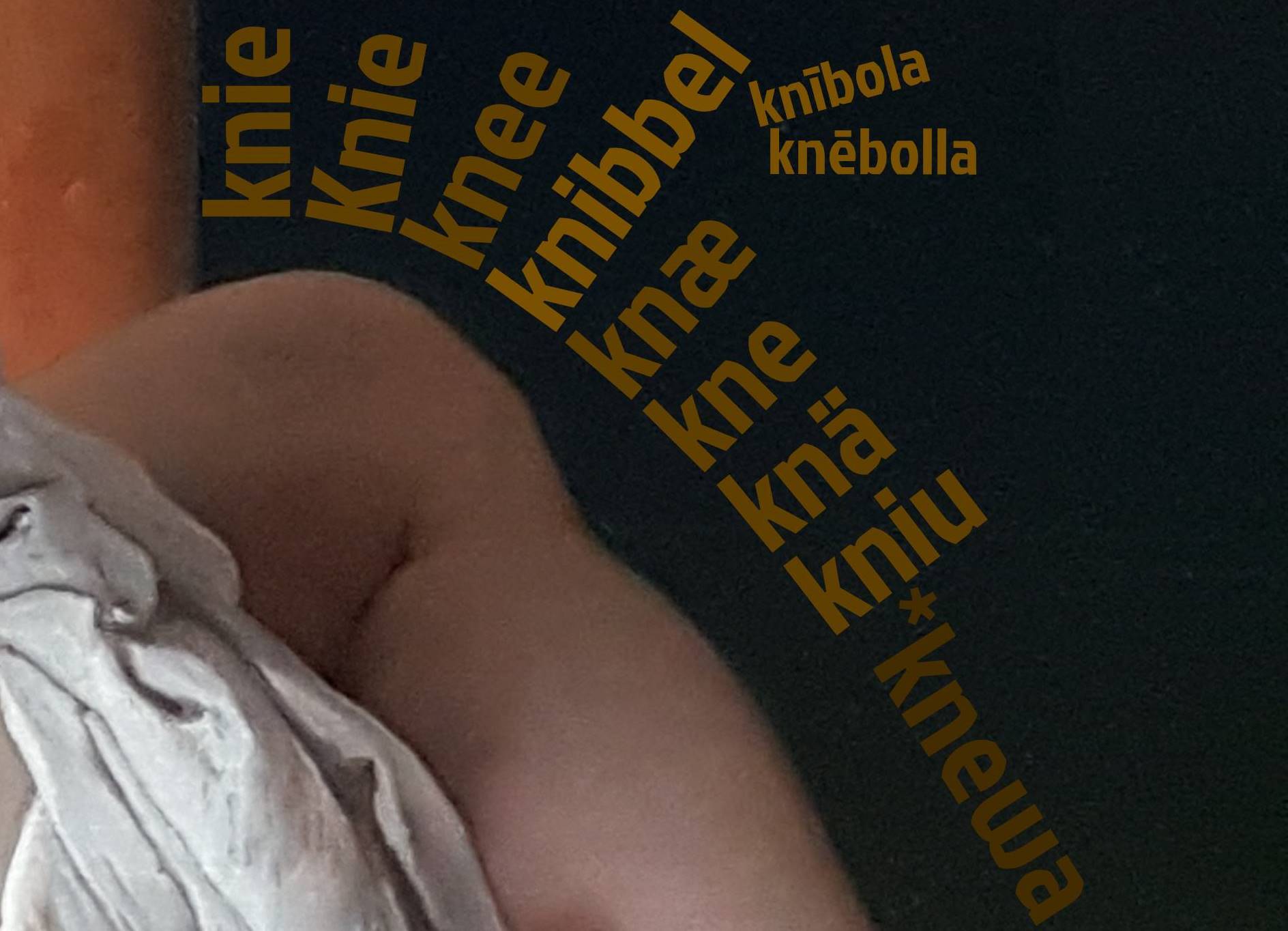

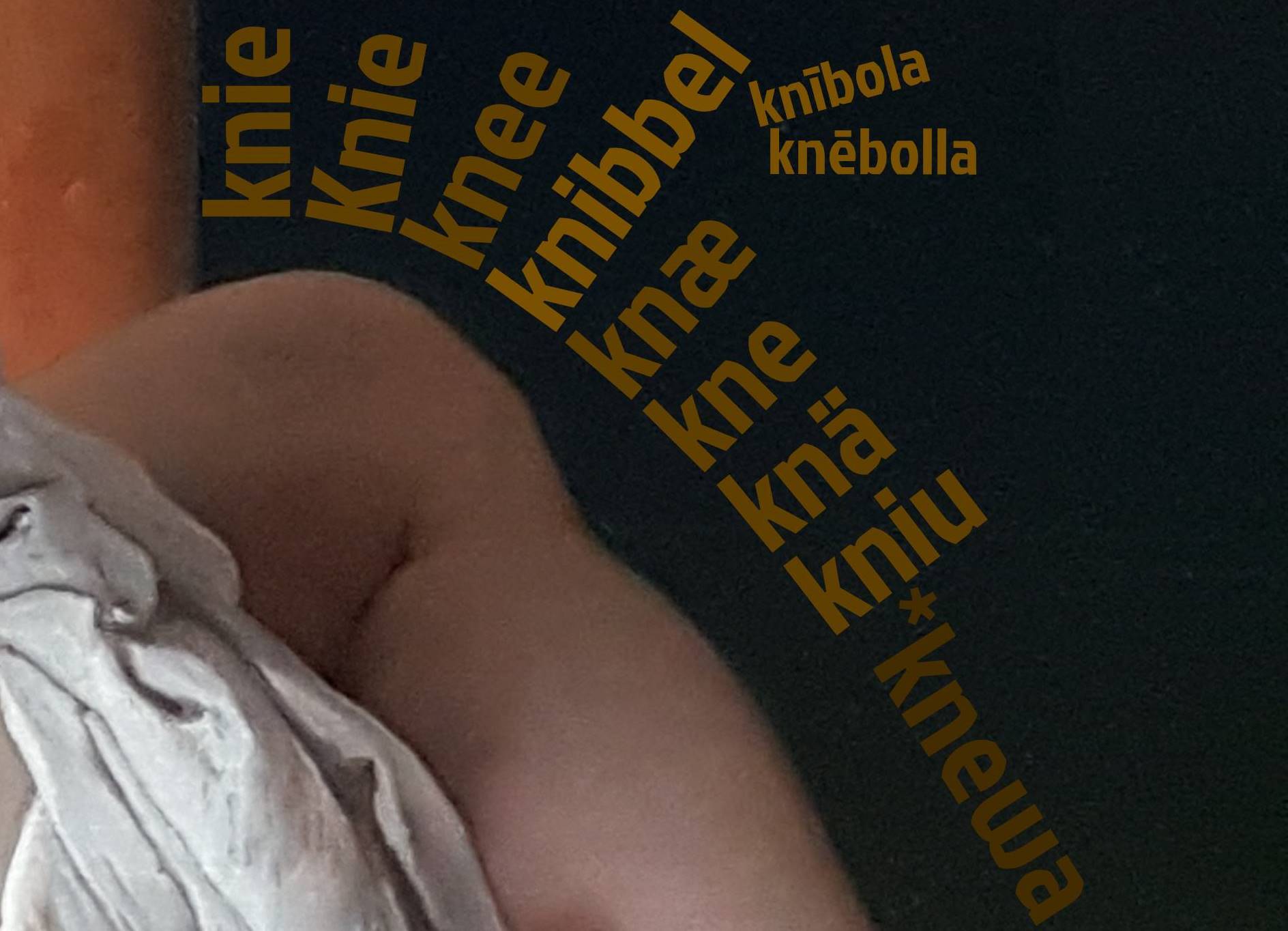

In Dutch we call the joint between the upper and lower leg a knie, just like the Germans; the only difference is that our eastern neighbours spell every noun with a capital letter, and thus write Knie. The English differs a little bit: there they write knee, but unlike the other Germanic languages they don't pronounce the k. On the other hand, the ee is pronounced somewhat like an /i/, as in Dutch and German.

In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish – all of them also Germanic languages, but just a different branch of the family tree – they pronounce the k, but after that there is a variant of the /e/ ("knay") or /Ɛ/ ("knè", with the vowel sounding abot the same as the "a" in "bad"). In written form we are talking about knæ, kne and knä respectively. The also Germanic but extinct Gothic language knew the word as kniu. Knowing all this, it should come as no surprise that all those words come from the same Protogermanic stem, in this case *knewa.

Remarkable deviation

It is therefore all the more remarkable that Frisian differs from the rest by calling the same joint knibbel. Indeed, with the same kni- at the beginning, but where does that -bel (pronunciation somewhere between /bəl/ and /bɔl/) come from? And did the Frisian word for knee always deviate like that, or did that only originate later?

To start with the last question: in Old Frisian (before 1550) there were the variants knī (with the pronunciation probably something that resembles the Dutch "knie") and knē (something like "knay"). The latter will have sounded almost the same as in New English around 1700. It was not until 1750 that the kn- in the English standard pronunciation was reduced to n-, after about a century of weakening and fading. By that time the word knē no longer existed in Frisian. There the word knibbel had already taken over, and it has remained that way to this day, as we saw earlier.

Kneecap and bread

Which brings us to the first question: where does that -bel in knibbel come from? The EWN mentions under the lemma "knee" the Old Frisian variants knībola and knēbolla with the meaning "knee(cap)". So with those words -bol(l)la has been added to the Old Frisian words we saw in the previous paragraph. The EWN doesn't examine the origin of this addition further, which in itself is of course logical for an "Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands" (Etymological Dictionary of Dutch). So I started to associate and because -bolla reminded me of the Dutch word bol ("ball, bulb, sphere, round object"), I looked that up.

The EWN does mention under "bol" the Old Frisian word bolla, which meant "(round) bread". This is clearly reflected in the contemporary Frisian word for bread: bôle. Delicious, but unfortunately no indication in the direction of the knee or kneecap. Fortunately, etymologiebank.nl also includes other dictionaries, including the Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek (Dutch Etymological Dictionary) from 1971. In that dictionary, kni-bola is mentioned under "bol" as Old Frisian word for "kneecap". Historically, you could therefore translate the Frisian word knibbel into Dutch as kniebol, or into English as kneeball or kneesphere.

The fact that the word for "kneecap" in Frisian has become the standard word for the entire knee, naturally means that another word is needed to indicate only the kneecap. Fortunately, the Frisians don't make a fuss about that: a kneecap is essentially a piece of bone in the knee, so that's how they call it: knibbelbonkje, or "little kneebone". Or actually "little kneeballbone".

Germanic unanimity

In Dutch we call the joint between the upper and lower leg a knie, just like the Germans; the only difference is that our eastern neighbours spell every noun with a capital letter, and thus write Knie. The English differs a little bit: there they write knee, but unlike the other Germanic languages they don't pronounce the k. On the other hand, the ee is pronounced somewhat like an /i/, as in Dutch and German.

In Danish, Norwegian and Swedish – all of them also Germanic languages, but just a different branch of the family tree – they pronounce the k, but after that there is a variant of the /e/ ("knay") or /Ɛ/ ("knè", with the vowel sounding abot the same as the "a" in "bad"). In written form we are talking about knæ, kne and knä respectively. The also Germanic but extinct Gothic language knew the word as kniu. Knowing all this, it should come as no surprise that all those words come from the same Protogermanic stem, in this case *knewa.

Remarkable deviation

It is therefore all the more remarkable that Frisian differs from the rest by calling the same joint knibbel. Indeed, with the same kni- at the beginning, but where does that -bel (pronunciation somewhere between /bəl/ and /bɔl/) come from? And did the Frisian word for knee always deviate like that, or did that only originate later?

To start with the last question: in Old Frisian (before 1550) there were the variants knī (with the pronunciation probably something that resembles the Dutch "knie") and knē (something like "knay"). The latter will have sounded almost the same as in New English around 1700. It was not until 1750 that the kn- in the English standard pronunciation was reduced to n-, after about a century of weakening and fading. By that time the word knē no longer existed in Frisian. There the word knibbel had already taken over, and it has remained that way to this day, as we saw earlier.

Kneecap and bread

Which brings us to the first question: where does that -bel in knibbel come from? The EWN mentions under the lemma "knee" the Old Frisian variants knībola and knēbolla with the meaning "knee(cap)". So with those words -bol(l)la has been added to the Old Frisian words we saw in the previous paragraph. The EWN doesn't examine the origin of this addition further, which in itself is of course logical for an "Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands" (Etymological Dictionary of Dutch). So I started to associate and because -bolla reminded me of the Dutch word bol ("ball, bulb, sphere, round object"), I looked that up.

The EWN does mention under "bol" the Old Frisian word bolla, which meant "(round) bread". This is clearly reflected in the contemporary Frisian word for bread: bôle. Delicious, but unfortunately no indication in the direction of the knee or kneecap. Fortunately, etymologiebank.nl also includes other dictionaries, including the Nederlands Etymologisch Woordenboek (Dutch Etymological Dictionary) from 1971. In that dictionary, kni-bola is mentioned under "bol" as Old Frisian word for "kneecap". Historically, you could therefore translate the Frisian word knibbel into Dutch as kniebol, or into English as kneeball or kneesphere.

The fact that the word for "kneecap" in Frisian has become the standard word for the entire knee, naturally means that another word is needed to indicate only the kneecap. Fortunately, the Frisians don't make a fuss about that: a kneecap is essentially a piece of bone in the knee, so that's how they call it: knibbelbonkje, or "little kneebone". Or actually "little kneeballbone".

*Nibble, nibble, little mouse, who’s that nibbling at my house?

WEST GERMANIC

In the West Germanic section, I regularly discuss a word that strikes me. I look at the meanings and forms of the word, and especially at where the word originates from. With that I compare the four West Germanic languages Dutch, English, Frisian and German, with the occasional inevitable trip across the fictional West Germanic border.

Sources

- Etymological dictionaries: etymologiebank.nl and Online Etymology Dictionary

- Google Translate

Image:

Own collage with a detail of Susanna at her bath (1850) by Francesco Hayez, photographed by me at The National Gallery in London.