ART PIECES

John Singer Sargent: Henry James

Visual Arts

| 21-10-2021

‘It looks like a photo!’ I hear a lady unknown to me say with admiration as she stands in front of the portrait. And certainly, if you walk up to the painting from a distance, you would almost think you are dealing with a photograph. But the closer you get and the closer you look, the more clearly you see that it doesn't look like a photo; and that is precisely what makes this work by John Singer Sargent so masterful.

"Real"

The woman who stood just before me at the portrait of Henry James will undoubtedly not be the only one who uses the word 'photo' in the beautiful exhibition Icons: Masterpieces from the National Portrait Gallery of the Fries Museum to indicate how "realistic" or "convincing" she finds a portrait. I think that's because many people see a photo as a realistic representation of reality: "in a photo you can see what something looks like in real". However, certainly in contemporary photography, that is of course open for debate, but that aside.

The similarity between a photo and a painting is that in both cases something spatial (three-dimensional) is converted into a flat surface (two-dimensional). So, when making a photo or painting you lose a dimension. Due to things like light and shadow, large and small, sharp and out of focus and linear perspective, you can suggest that you are looking at a spatial representation on that flat surface. All those "tricks" are therefore summarized with the concept of the suggestion of space. Some of those things you get as a free gift from your camera when you take a picture. However, a skilled artist – whether a photographer or a painter – knows how to manipulate everything in such a way that the desired effect is ultimately achieved.

A skilled painter

Certainly in the time of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), taking a photo was mainly a matter of registration, while a painting involves interpretation. A skilled painter knows how to direct the viewer's gaze. It goes without saying that Sargent was skilled. He is best known for his portraits, of which you can view a nice overview here, but also painted landscapes and other scenes. Sargent was very prolific: in total he made about 900 oil paintings, 2000 watercolors and countless sketches and charcoal drawings. Much of those originated in Europe, for although Sargent had American parents, he was born in Florence and grew up in several European countries.

In 1884, in Paris, Sargent met writer Henry James (1843-1916), who was born in America but, like Sargent, spent much of his childhood in Europe. That is not the only common ground between the two men; they understood each other perfectly and their points of view were identical in many respects. They would remain good friends for the rest of their lives and also had many mutual friends and acquaintances. For example, James introduced Sargent to Isabella Stewart Gardner, an American art collector. Her collection, which can be seen in the museum named after her, includes a number of portraits that Sargent made of her. Henry James wrote laudatory pieces for Sargent's work, while remaining critical, and introduced him to potential clients in London and Boston. It is no exaggeration to say that Sargent's life would have been very different without Henry James.

Appearances are deceiving

When a group of his friends decided to have Henry James portrayed on the occasion of his 70th birthday, it was only natural that John Singer Sargent would paint that portrait. You'd think an accomplished artist like Sargent would pick it up with ease, but he confided in James that he hadn't painted portraits for three or four years and that he had "lost his nerve" about it. Once he had started, however, he got into his stride. When you look at the painting, you get the impression that it has been put on canvas quite effortlessly, partly because of the loose brushstrokes that Sargent uses for a large part of the painting. But there too appearances are deceiving: James has sat about ten times for this portrait.

That loose touch is not only a hallmark of Sargent's work, but also one of the reasons why I don't think this painting looks like a photograph. A photo camera captures all the details and makes no distinction. The work of painters who work in this way is often called photo-realistic for a reason. Sargent, on the other hand – and many painters with him – does make a distinction: he works out some parts in more detail than the other. For example, look at the eyes in this portrait: the iris and pupil form one equally dark "spot" with the drop shadow of the upper eyelid, on which no eyelashes can be found. Your brain supplements the information provided by the painting, allowing Sargent to very consciously omit some of that information and thus direct your gaze.

Another detail from which the above shows very nicely, I think, is the checkered pattern on the waistcoat and the chain that runs across it at the bottom. If you zoom in on that, you see a very loose touch; so loose that it is actually no longer a credible expression of texture. But in the whole of the canvas it works perfectly, as if you focus on the face and blur everything around it. On this page you can view a good quality photo of the painting, where you can also zoom in on details. Of course, that still doesn't compare to the real work, which can be seen in Leeuwarden until January 9, 2022 and then, I assume, again in London. Henry James would no doubt recommend that too. He said of the portrait: 'Sargent at his very best and poor old H.J. not at his worst; in short a living breathing likeness and a masterpiece of painting.' I have nothing to add to that.

"Real"

The woman who stood just before me at the portrait of Henry James will undoubtedly not be the only one who uses the word 'photo' in the beautiful exhibition Icons: Masterpieces from the National Portrait Gallery of the Fries Museum to indicate how "realistic" or "convincing" she finds a portrait. I think that's because many people see a photo as a realistic representation of reality: "in a photo you can see what something looks like in real". However, certainly in contemporary photography, that is of course open for debate, but that aside.

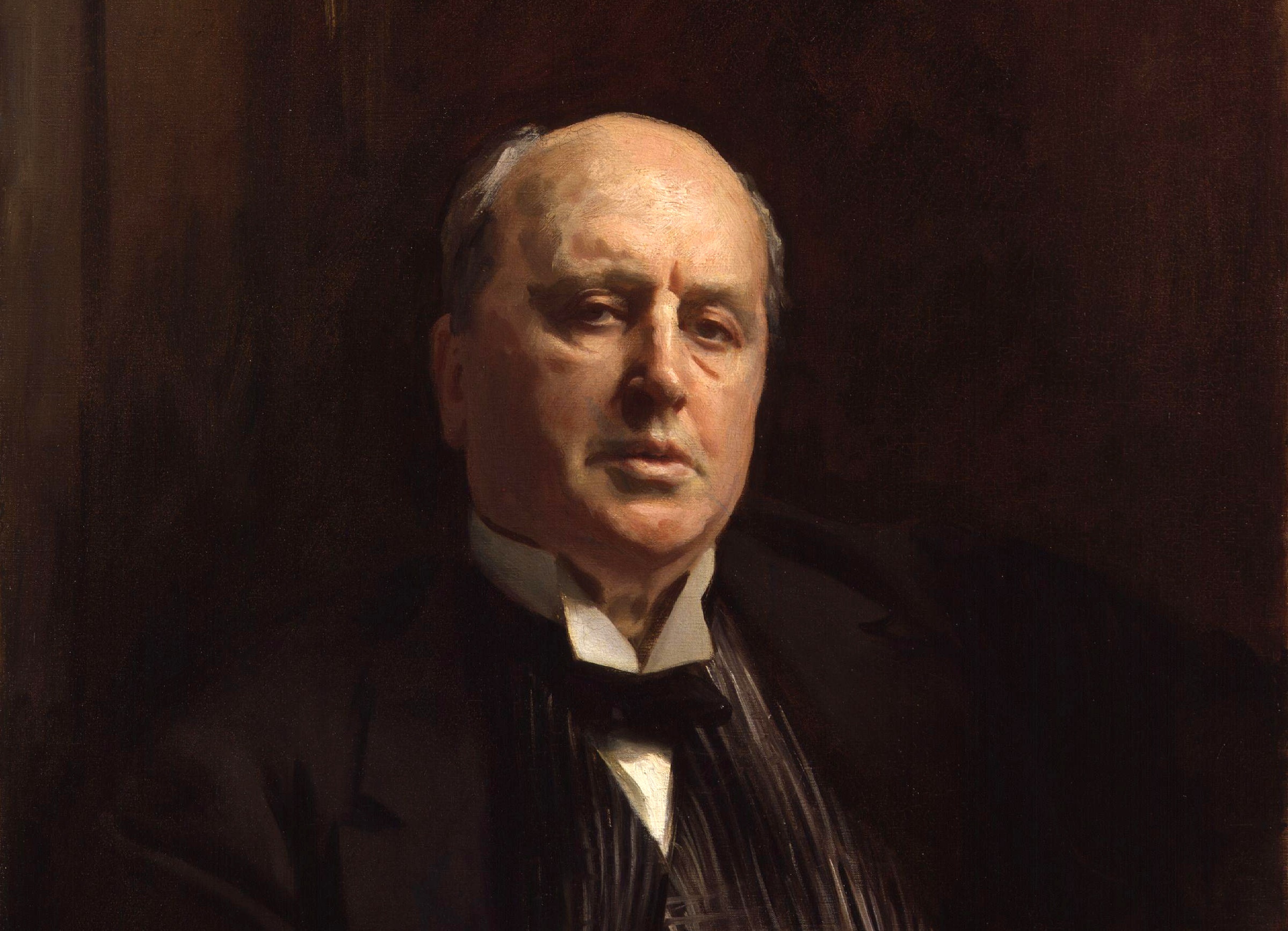

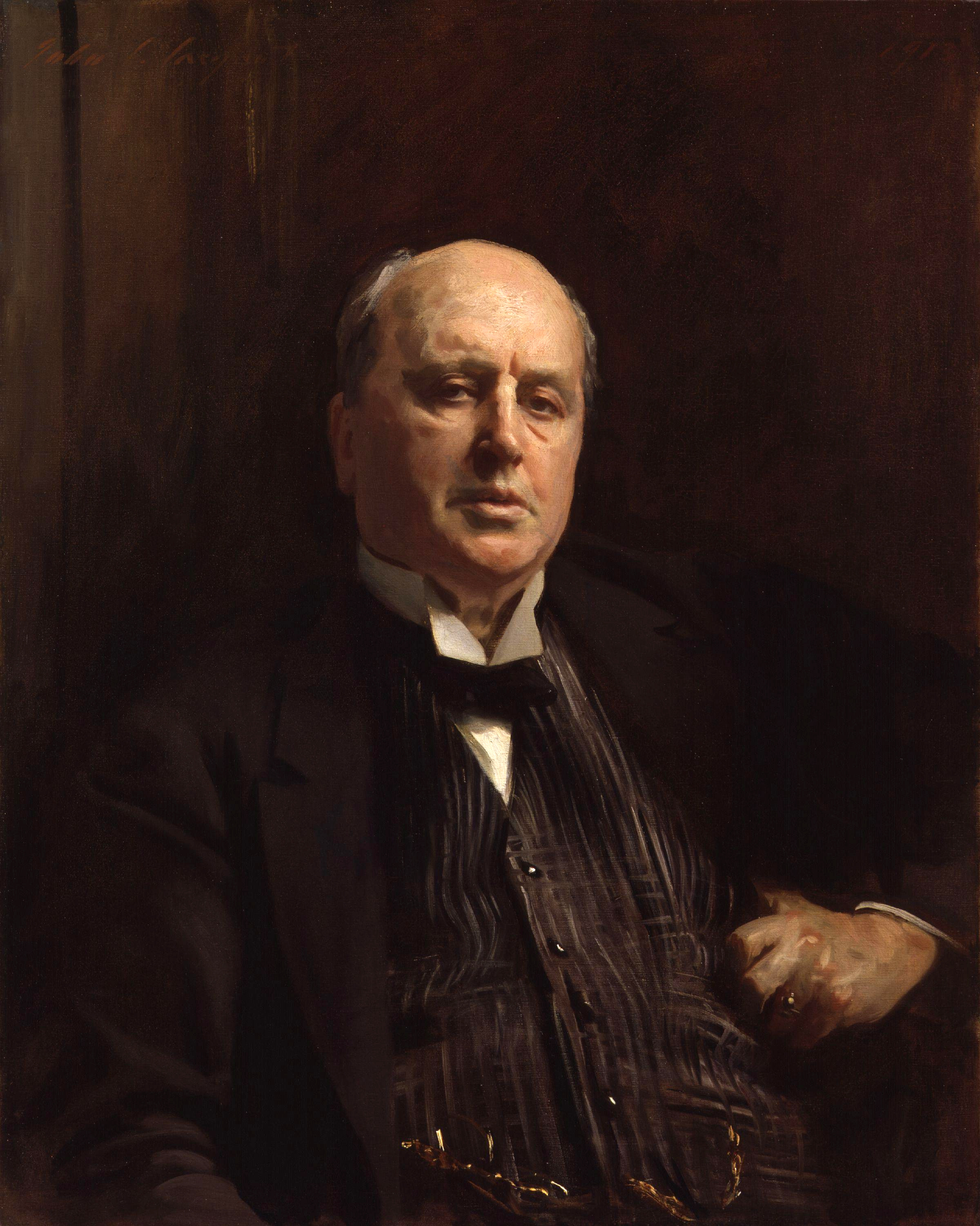

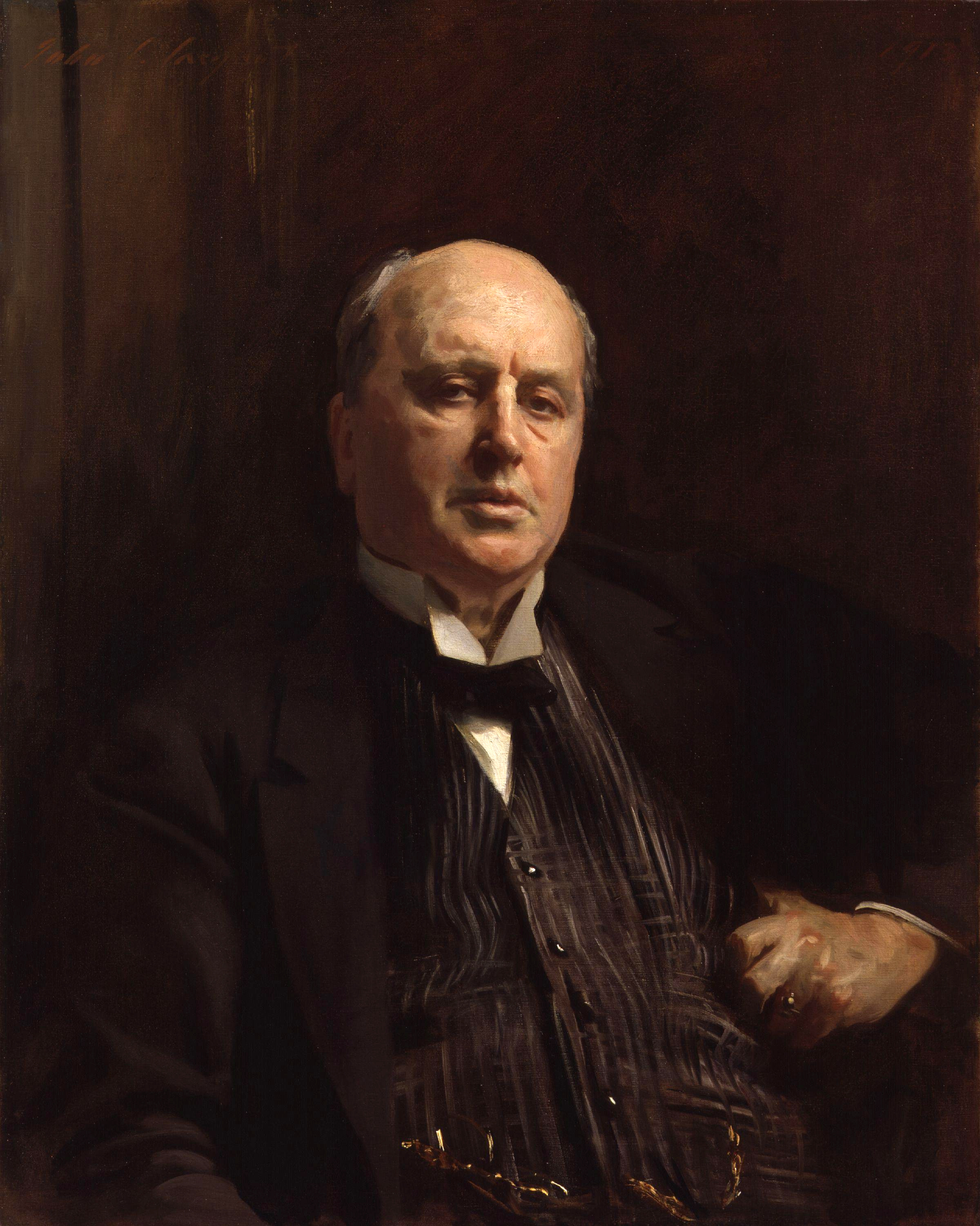

John Singer Sargent, Henry James (oil on canvas, 1913)

Suggestion of spaceThe similarity between a photo and a painting is that in both cases something spatial (three-dimensional) is converted into a flat surface (two-dimensional). So, when making a photo or painting you lose a dimension. Due to things like light and shadow, large and small, sharp and out of focus and linear perspective, you can suggest that you are looking at a spatial representation on that flat surface. All those "tricks" are therefore summarized with the concept of the suggestion of space. Some of those things you get as a free gift from your camera when you take a picture. However, a skilled artist – whether a photographer or a painter – knows how to manipulate everything in such a way that the desired effect is ultimately achieved.

A skilled painter

Certainly in the time of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), taking a photo was mainly a matter of registration, while a painting involves interpretation. A skilled painter knows how to direct the viewer's gaze. It goes without saying that Sargent was skilled. He is best known for his portraits, of which you can view a nice overview here, but also painted landscapes and other scenes. Sargent was very prolific: in total he made about 900 oil paintings, 2000 watercolors and countless sketches and charcoal drawings. Much of those originated in Europe, for although Sargent had American parents, he was born in Florence and grew up in several European countries.

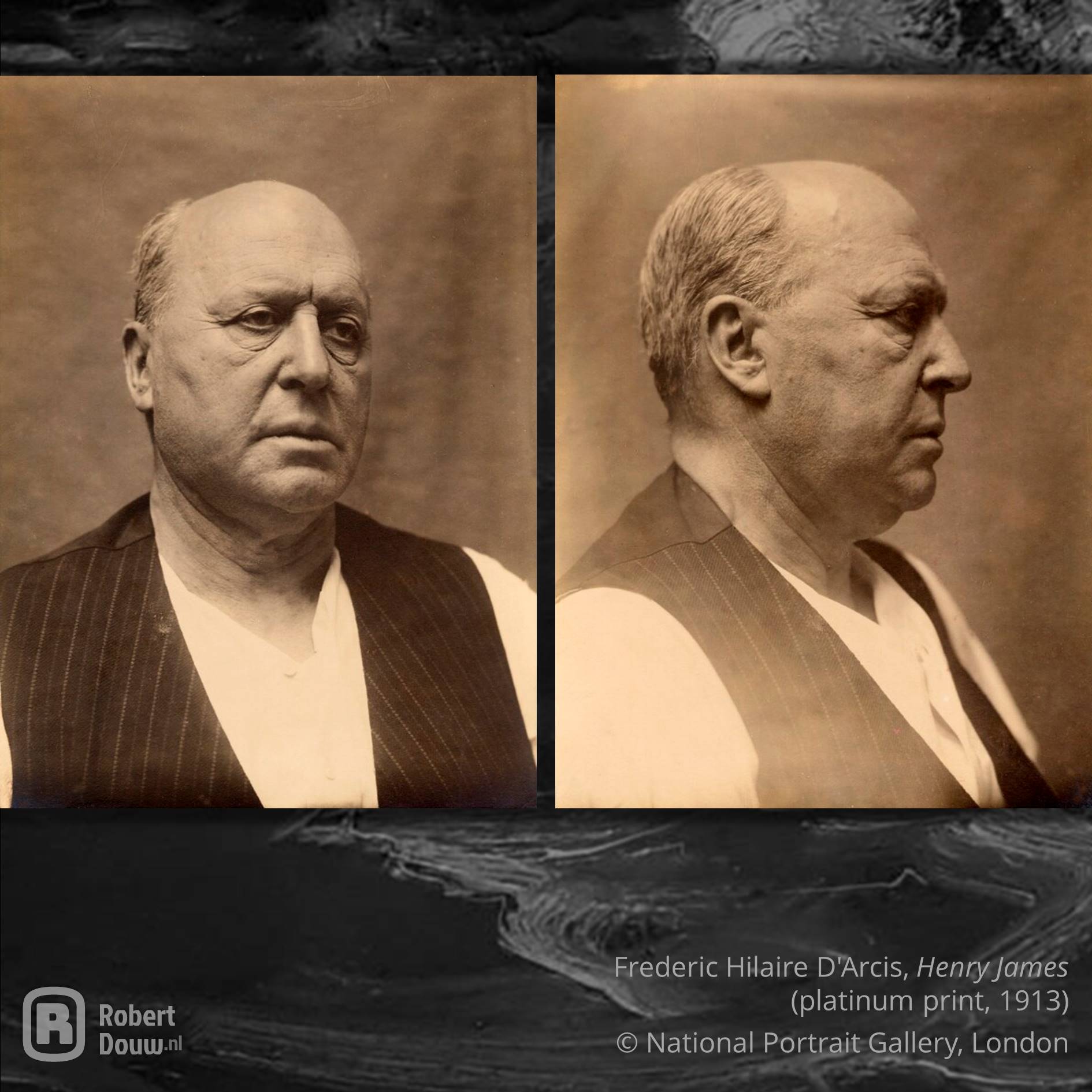

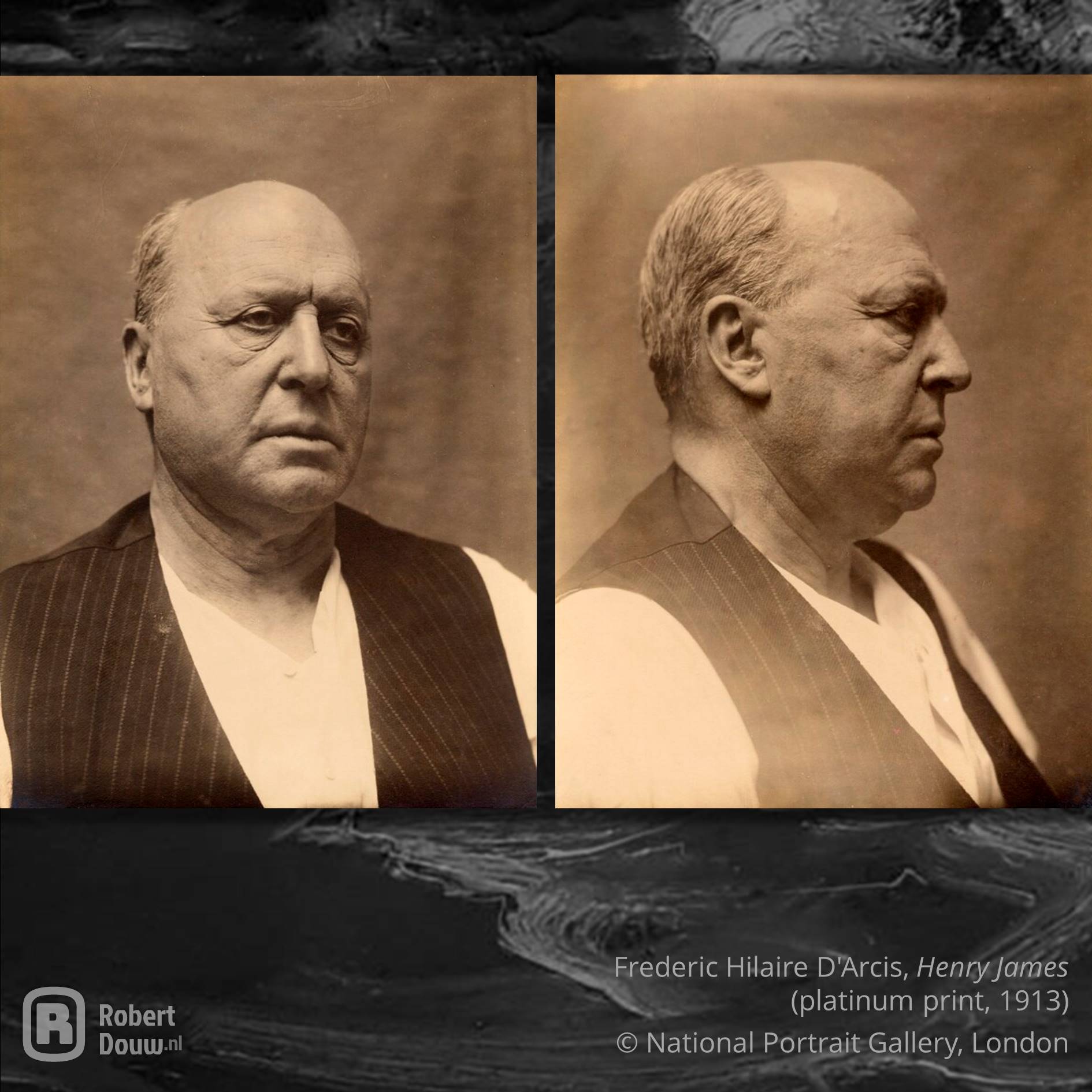

Photographic Portrait of Henry James by Frederic Hilaire D'Arcis

Henry JamesIn 1884, in Paris, Sargent met writer Henry James (1843-1916), who was born in America but, like Sargent, spent much of his childhood in Europe. That is not the only common ground between the two men; they understood each other perfectly and their points of view were identical in many respects. They would remain good friends for the rest of their lives and also had many mutual friends and acquaintances. For example, James introduced Sargent to Isabella Stewart Gardner, an American art collector. Her collection, which can be seen in the museum named after her, includes a number of portraits that Sargent made of her. Henry James wrote laudatory pieces for Sargent's work, while remaining critical, and introduced him to potential clients in London and Boston. It is no exaggeration to say that Sargent's life would have been very different without Henry James.

Appearances are deceiving

When a group of his friends decided to have Henry James portrayed on the occasion of his 70th birthday, it was only natural that John Singer Sargent would paint that portrait. You'd think an accomplished artist like Sargent would pick it up with ease, but he confided in James that he hadn't painted portraits for three or four years and that he had "lost his nerve" about it. Once he had started, however, he got into his stride. When you look at the painting, you get the impression that it has been put on canvas quite effortlessly, partly because of the loose brushstrokes that Sargent uses for a large part of the painting. But there too appearances are deceiving: James has sat about ten times for this portrait.

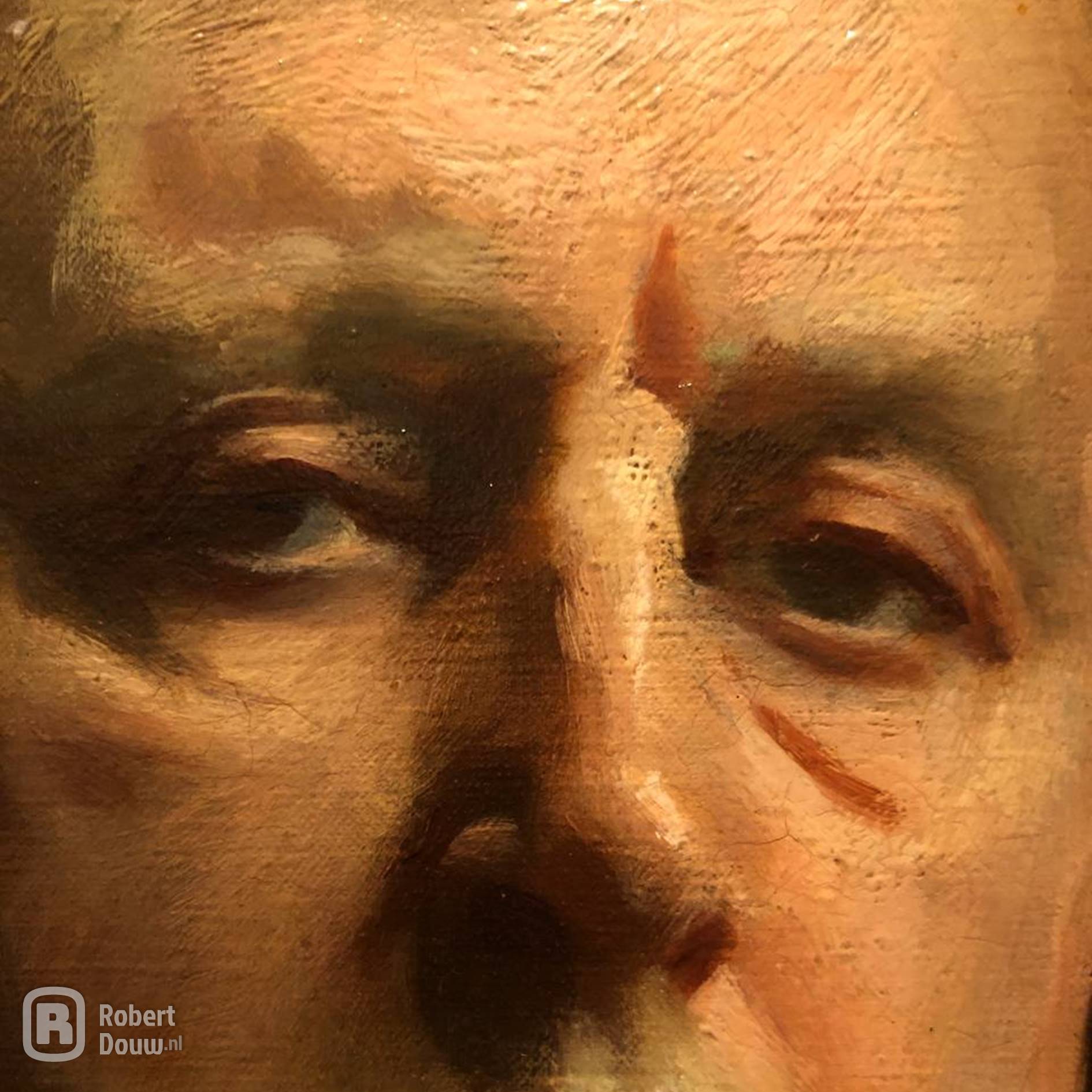

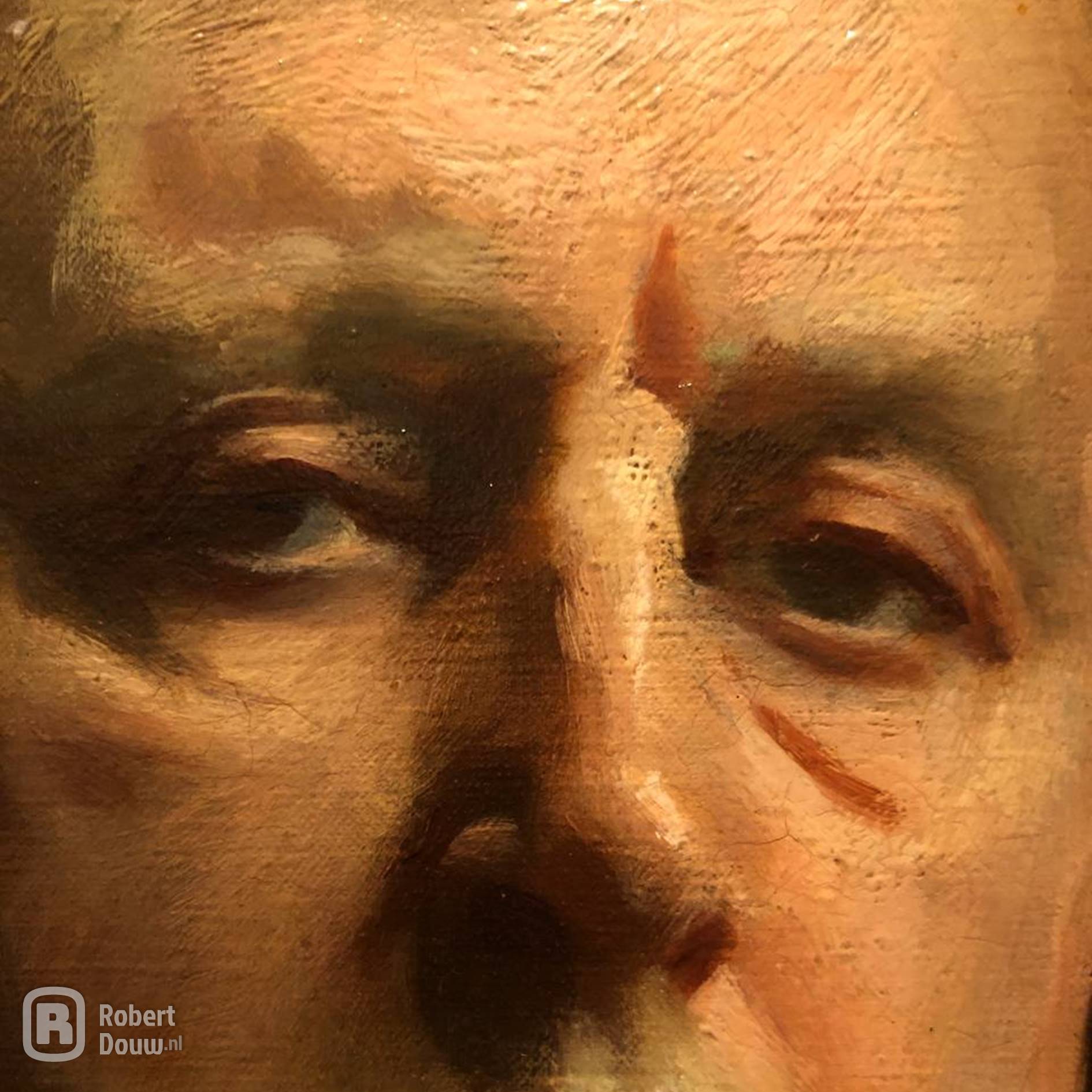

John Singer Sargent, Henry James (oil on canvas, 1913, detail)

No photographThat loose touch is not only a hallmark of Sargent's work, but also one of the reasons why I don't think this painting looks like a photograph. A photo camera captures all the details and makes no distinction. The work of painters who work in this way is often called photo-realistic for a reason. Sargent, on the other hand – and many painters with him – does make a distinction: he works out some parts in more detail than the other. For example, look at the eyes in this portrait: the iris and pupil form one equally dark "spot" with the drop shadow of the upper eyelid, on which no eyelashes can be found. Your brain supplements the information provided by the painting, allowing Sargent to very consciously omit some of that information and thus direct your gaze.

John Singer Sargent, Henry James (oil on canvas, 1913, detail)

A living breathing likenessAnother detail from which the above shows very nicely, I think, is the checkered pattern on the waistcoat and the chain that runs across it at the bottom. If you zoom in on that, you see a very loose touch; so loose that it is actually no longer a credible expression of texture. But in the whole of the canvas it works perfectly, as if you focus on the face and blur everything around it. On this page you can view a good quality photo of the painting, where you can also zoom in on details. Of course, that still doesn't compare to the real work, which can be seen in Leeuwarden until January 9, 2022 and then, I assume, again in London. Henry James would no doubt recommend that too. He said of the portrait: 'Sargent at his very best and poor old H.J. not at his worst; in short a living breathing likeness and a masterpiece of painting.' I have nothing to add to that.

Omnibus

Anders Zorn

Lake Keitele

Akseli Gallen-Kallela

VISUAL ARTS

Click here for an overview of everything in the Visual Arts section.