WEST GERMANIC

Labour and do work

Linguistics

| 04-09-2020

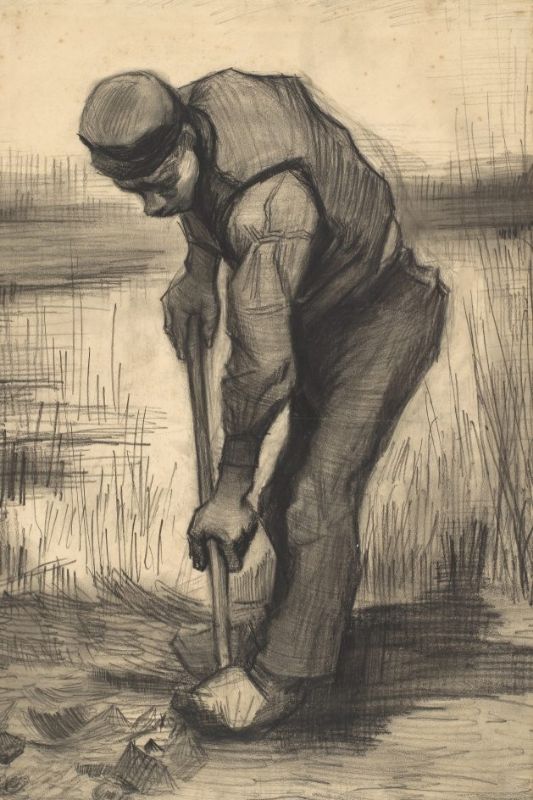

Digger, Vincent van Gogh (1885)

Difference between labour and workEvery weekday morning I leave my house to go to werk (work), and after a day of werken (work) as an werknemer (employee) I go home again. I would never say that I go to arbeid (labour) to arbeiden (labour) as an arbeider (labourer). To me those words belong more to plodding craftsmen like blacksmiths, peat cutters and farmhands. The word arbeider evokes associations with the rise of socialism and the Industrial Revolution rather than with the present day. Why is that? And why don't I think concepts such as collectieve arbeidsovereenkomst (collective labour agreement), arbeidstijdverkorting (working time reduction) and arbeidsmarkt (labour market) sound old-fashioned?

It's not new that there's a difference between arbeid (labour) and werk (work). The EWN mentions the Wachtendonckse Psalmen from the 10th century as the oldest site of the word arbeid, and for werk it mentions a source from the end of the 8th century. The word werk has a Protogermanic root *werka-, which can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root *werg-. Simply put: the word werk has been around for centuries in a very recognizable form. The word arbeid is probably taken from High German, and is described in the EWN as a 'general Germanic word', with a possible relationship to some words outside of Germanic. At first, arbeid was mainly understood to mean 'the pain, the torment that was done to someone, the distress in which he was,' I read in the EWN at P.H. Schröder, who goes on to say that it is mainly due to Luther that the second pre-existing meaning 'the effort one employs to achieve a goal' has come to the fore.

Labour and do all your work

The words arbeid and werk reminded me of a phrase from Exodus 20, the Ten Commandments. Because Bible translations can be illustrative of the linguistic usage, I decided to compare several Dutch translations1 side by side. I grew up with the 1951 translation of the Dutch Bible Society, knowing the passage in question as "zes dagen zult gij arbeiden en al uw werk doen", which happens to be a literal translation of the same sentence in the 1952 Revised Standard Version: "Six days you shall labour, and do all your work." In the Statenvertaling it is also stated like this.

The difference between arbeiden (labour) and uw werk doen (doing your work) is completely eliminated in the Groot Nieuws Bijbel: "Zes dagen heb je om te werken" ("You have six days to work"). In this case, I find the Bijbel in Gewone Taal more beautiful and complete, in which is chosen for the translation “Zes dagen mogen jullie werken en bezig zijn met alles wat je moet doen” (“Six days you can work and be busy with everything you have to do”). So there the old arbeid (labour) is replaced with werken (work) and al uw werk (all your work) with alles wat je moet doen (everything you have to do). That feels like a logical contemporary representation to me. In the Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling is chosen for “Zes dagen lang kunt u werken en al uw arbeid verrichten” (“For six days you can work and do all your labour”) – a little confusing, I think. Nevertheless, perhaps this reversal of arbeid and werk also shows something of the shift in emotional value associated with those words.

What's also telling for the word arbeid becoming less common is, in my opinion, the fact that this word appears 75 times in the 1977 Statenvertaling, only 14 times in the 2007 Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling and not at all anymore in the 2014 Bijbel in Gewone Taal. I think that shift has to do with the changed labour relations, to use an appropriate word. I think that these days arbeiden generally feels more like toil on behalf of a boss, because you have to make a living. Werken, on the other hand, is more in keeping with how we like to see it nowadays: in a nice job, with an equal employer. In Dutch anyway, because in Frisian it is still more common in my opinion to talk about de baas ('the boss'), although also in Frisian I rarely hear the word arbeidzje there, in contrast to wurkje.

Labour, work, Arbeit

For as far as I can tell, to work is also more common in English than to to labo(u)r. Only in German is it the other way around: the DWDS indicates at werken that arbeiten is the main form. Just a sample survey: in the Van Dale study dictionary English-Dutch I count 19 entries with labour(-), while in the Van Dale study dictionary German-Dutch there are no fewer than 145 entries with arbeit(-). Since Werk also means 'factory' in German, it doesn't make much sense to count the entries with werk(-), but I think the picture is clear. In the Van Dale medium dictionary Dutch (comparable in size to the study dictionary) I find 56 entries with arbeid(-), in the study dictionary Dutch-English there are 38. So Dutch ends up somewhere between English and German. This includes many compositions with arbeid-, which are largely translated into English as work, employment or job.

This sample survey is of course far from scientific and therefore I won't draw big conclusions from it, but it is a striking picture. Above all, it illustrates very clearly how much language has to do with feeling and association. For example, when I think of English labour, I mainly think of the political party and the election posters I saw as a child on holiday in England: Vote Labour. That the meaning of words has to do with association, however, is most apparent to me with the German word Arbeit; while that is a very everyday word for native German speakers, I know it primarily from the gates of concentration and extermination camps. And that makes the word sound completely different...

WEST GERMANIC

In the West Germanic section, I regularly discuss a word that strikes me. I look at the meanings and forms of the word, and especially at where the word originates from. With that I compare the four West Germanic languages Dutch, English, Frisian and German, with the occasional inevitable trip across the fictional West Germanic border.

Sources

1debijbel.nl

- Statenvertaling (1977/2010-2017, originally form 1637): 'States Translation', somewhat comparable to the King James Version;

- NGB51: translation of the Nederlands Bijbelgenootschap (Dutch Bible Society), somewhat comparable to the 1952 Revised Standard Version of The Holy Bible;

- Groot Nieuws Bijbel (1982/1996): literally 'Big News Bible', a Bible in 'today's Dutch', somewhat comparable to the New International Version;

- Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling (2004/2007): New Bible Translation, the current standard translation in many Dutch churches;

- Bijbel in Gewone Taal (2014): 'Plain Language Bible'.

For writing this piece, I also used etymologiebank.nl, taalweb.frl, dwds.de, etymonline.com and the mentioned Van Dale dictionaries.

Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).