ART PIECES

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Lake Keitele

Visual arts

| 21-05-2021

Until recently I had never heard of Akseli Gallen-Kallela, also not under his birth name Axel Gallén. I suspect it was somewhere in 2018 that I saw a painting of a lake on Instagram that really appealed to me. The artist's name was underneath as a hashtag, so I decided to follow that hashtag.

Between abstraction and figuration

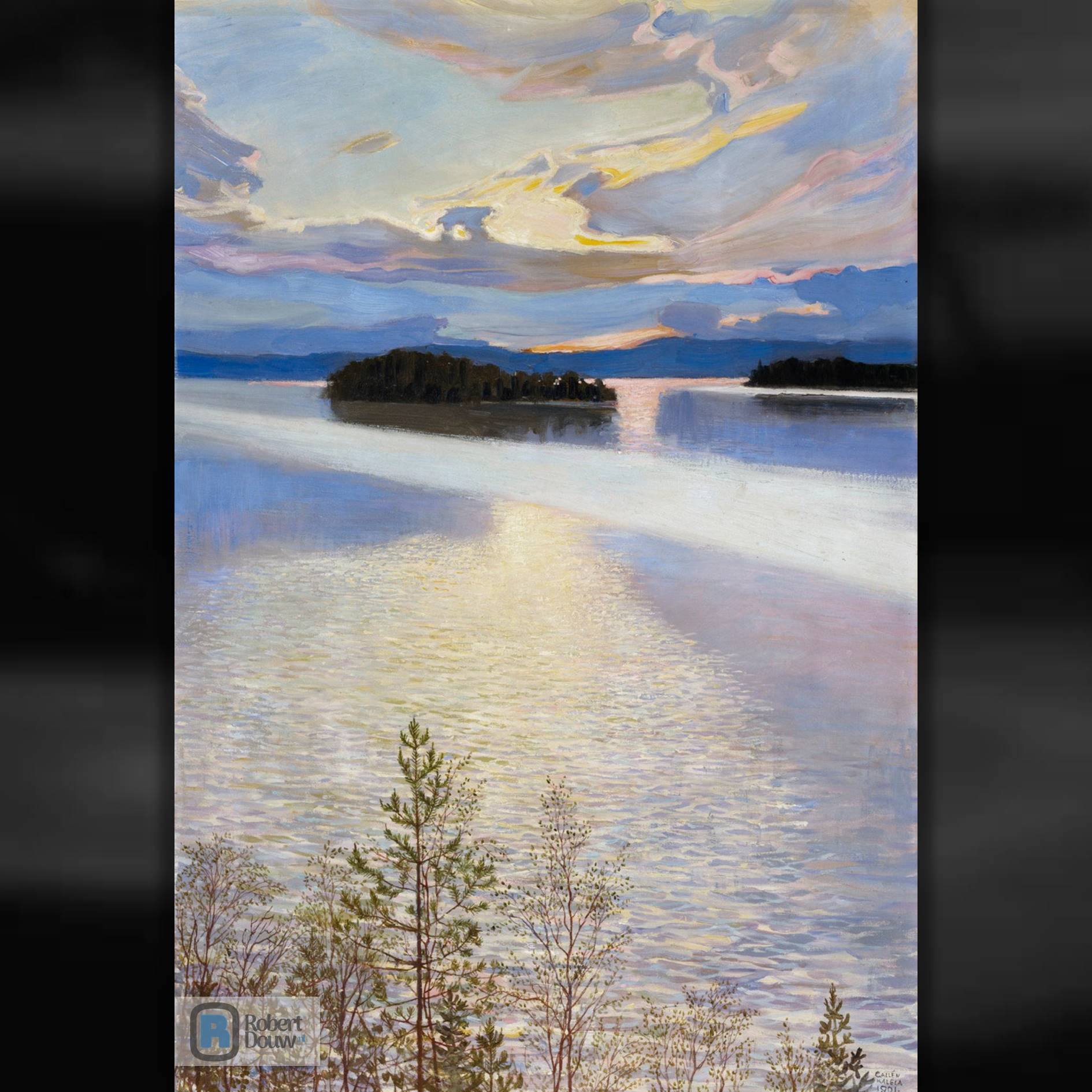

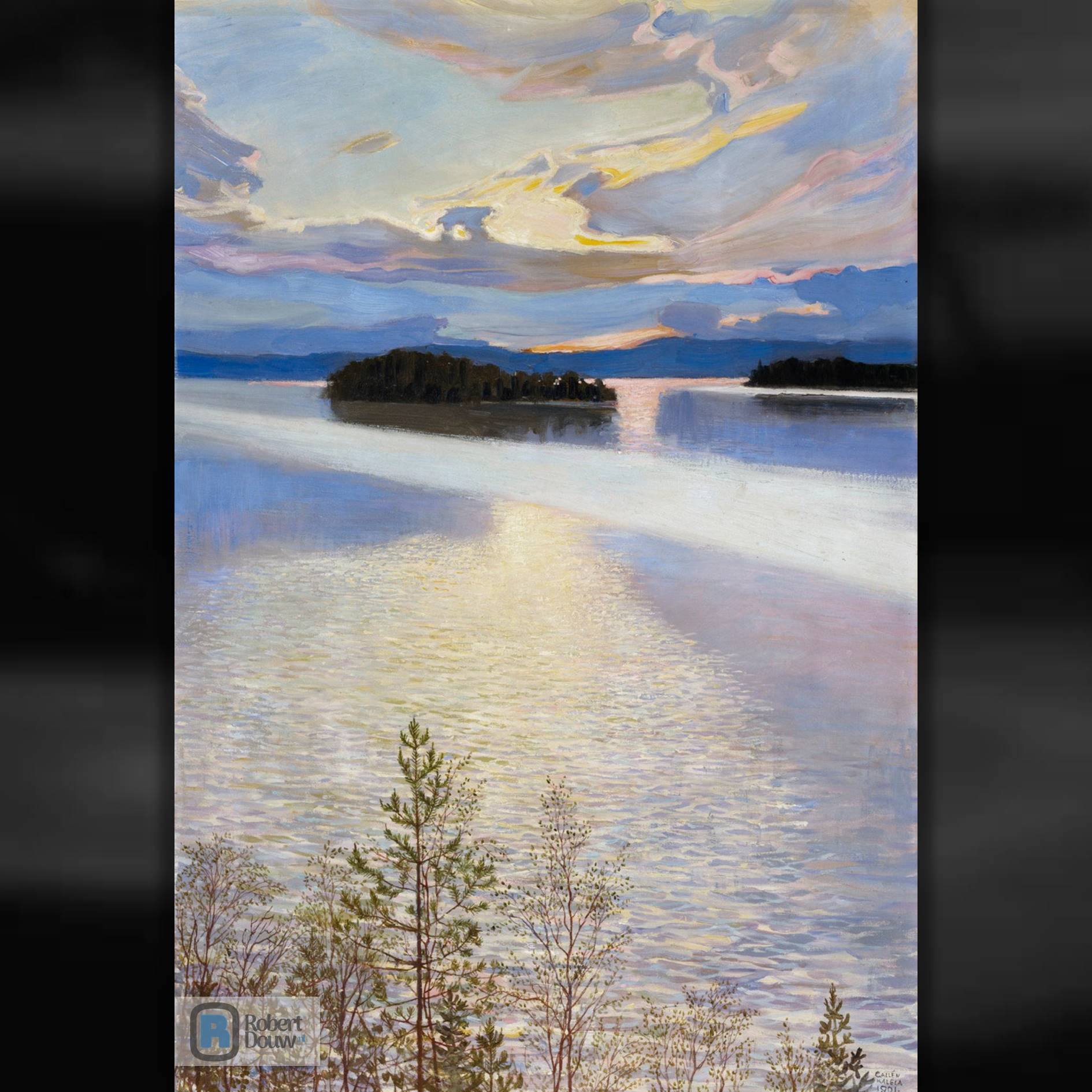

Whatever work came by using the hashtag #akseligallenkallela, that one painting of that lake kept popping out. The cool, greyish blue colors appealed to me, but also those striking light stripes over the water. Although it is without a doubt a figurative painting – everyone will recognize a lake with an island in it – those light stripes also give the painting something abstract. The bottom two-thirds of the canvas would be an abstract work without the top part, with the island, the forest in the background and the cloudy sky. I love the tension between abstraction and figuration, which you can also find in a number of Mondrian landscapes, for example.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) leaves school in 1881 to devote himself entirely to his art studies. From 1884 he studies in Paris. He would live in that city for several periods, interspersed with some parts of his homeland Finland, and with Berlin, Florence, Vienna, Hungary, Nairobi and the United States, among other places. In 1900 he contributes to the Finnish Pavilion at the Paris World's Fair, with four frescoes, an interior design and more, which earns him two gold and two silver medals. In 1914 the Uffizi in Florence commissiones him to create a self-portrait. The last major work he completes, in 1928, are the frescoes in the National Museum in Helsinki. Akseli Gallen-Kallela dies of pneumonia in Stockholm on 7 March 1931. In Finland he is given a state funeral. During his life, Finland became an independent republic and Gallen-Kallela made an important contribution to national consciousness with his work.

With the biography of a few sentences in the previous paragraph, I obviously do Gallen-Kallela short, and that also applies to what I tell about his work in this article. His oeuvre is so extensive and diverse – in terms of subject and place of origin as well as in style and technique – that I can only discuss a fraction in this piece. My starting point with that is the wonderful reflection on the water, caused by the wind, which gives Lake Keitele not only abstract features, but also a lot of spaciousness, and evokes the atmosphere of being outside, on or near the water, where a cool breeze carries along the smell of the trees.

The oldest work by Gallen-Kallela on which this reflection struck me is the middle part of the triptych Aino Myth, which he painted in 1891. In 1888-1889 Gallen-Kallela made the first version of this triptych about an episode from the Finnish heroic epic the Kalevala, but on that version there's no reflection. In the version from 1891 it is there and the reflection contributes to the more dreamy atmosphere of this version, for which his fresh wife Mary Slöör was the model. In terms of composition, the reflection may not be the best addition here: due to the greater emphasis on the landscape, the attention is somewhat distracted from the story of Aino and Väinämöinen.

Subsequently, such a reflection can be seen on landscape paintings a number of times, such as Lake View from 1901, which I think is also a beautiful painting. Unlike on Lake Keitele, Gallen-Kallela sticks to one stripe of reflection, which applies to more of his landscapes. Yet that one stripe is enough to suggest a lot of space, especially as a diagonal that tapers slightly in the distance, as in Lake View. On The Sauna Girl from 1904 as well, only one stripe of reflection can be seen, this time as an underline of the horizon to which it runs parallel. The background, with the lake and the wooded island, suggests that the location is the same as where Lake Keitele was painted. Gallen-Kallela clearly liked that place – and who can blame him? – which he also painted several times as an independent subject, including on this version with a rowing boat, from 1919.

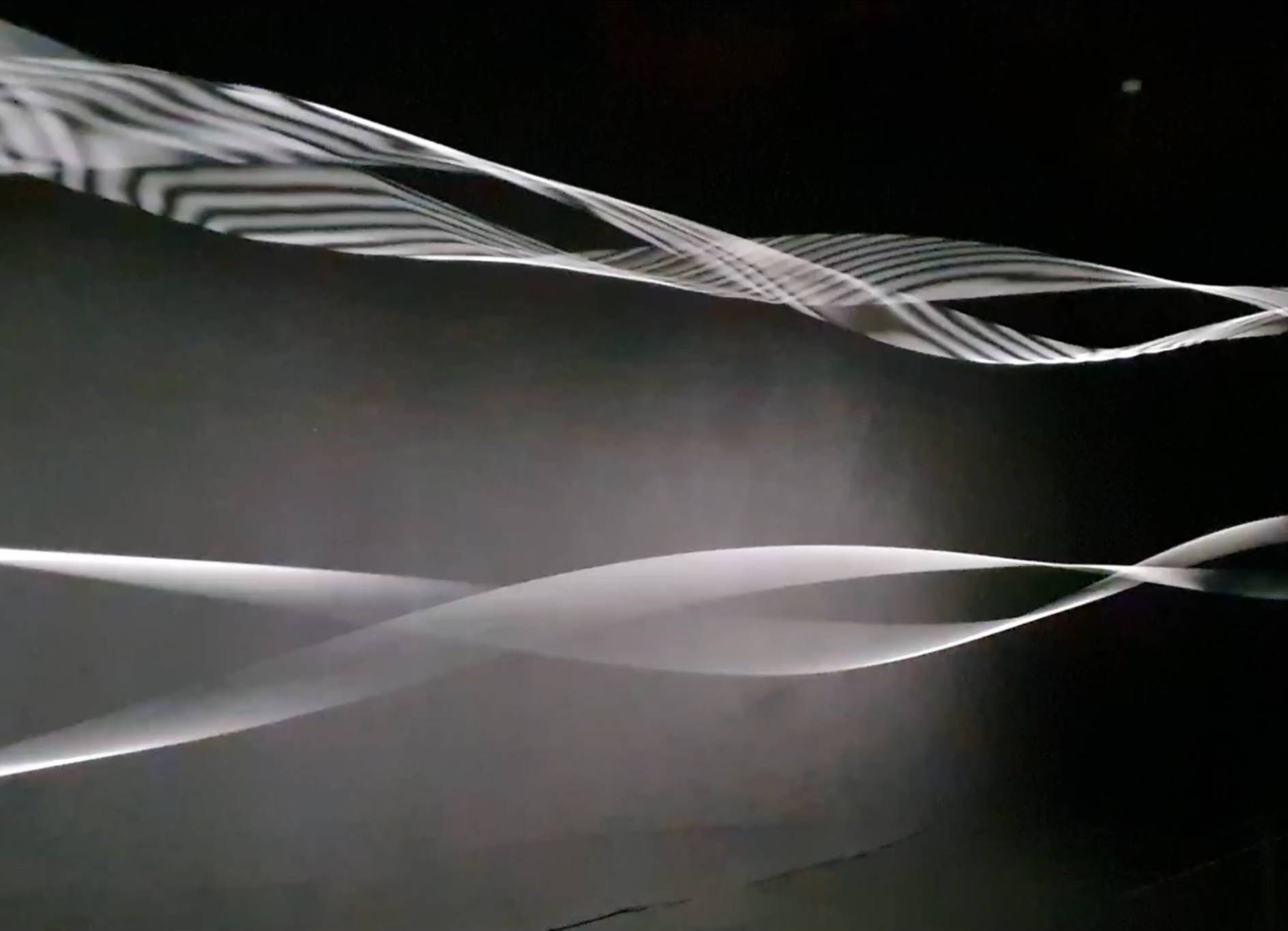

When I unsuspectingly walked through the National Gallery in London in August 2019, I suddenly saw Lake Keitele. The canvas was slightly larger than I expected (53 x 66 cm) and above all less "smooth" than I thought based on photos on Instagram. That's of course also one of the main reasons to look at visual work in real life: the format, the use of color, the touch and more of such very determining things you do not see well in a photo. With the detailed photos above and below I try to give a bit of an impression nonetheless (with which you should take into account that a small shadow from the frame falls over the clouds). Gallen-Kallela painted especially the clouds quite thick, while you would expect that pasty use of paint in the foreground rather than in the background of a painting. The paint has been applied quite thinly from the trees in the background down to the center of the painting; there you can clearly see the texture of the canvas through the paint. In the hatchings below you can again clearly see the brushstroke, but the paint is still applied less thickly than with the clouds. You don't see all that very well in photos. So if it's allowed again: just watch it for real!

Between abstraction and figuration

Whatever work came by using the hashtag #akseligallenkallela, that one painting of that lake kept popping out. The cool, greyish blue colors appealed to me, but also those striking light stripes over the water. Although it is without a doubt a figurative painting – everyone will recognize a lake with an island in it – those light stripes also give the painting something abstract. The bottom two-thirds of the canvas would be an abstract work without the top part, with the island, the forest in the background and the cloudy sky. I love the tension between abstraction and figuration, which you can also find in a number of Mondrian landscapes, for example.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Lake Keitele (1905)

Finnish citizen of the worldAkseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) leaves school in 1881 to devote himself entirely to his art studies. From 1884 he studies in Paris. He would live in that city for several periods, interspersed with some parts of his homeland Finland, and with Berlin, Florence, Vienna, Hungary, Nairobi and the United States, among other places. In 1900 he contributes to the Finnish Pavilion at the Paris World's Fair, with four frescoes, an interior design and more, which earns him two gold and two silver medals. In 1914 the Uffizi in Florence commissiones him to create a self-portrait. The last major work he completes, in 1928, are the frescoes in the National Museum in Helsinki. Akseli Gallen-Kallela dies of pneumonia in Stockholm on 7 March 1931. In Finland he is given a state funeral. During his life, Finland became an independent republic and Gallen-Kallela made an important contribution to national consciousness with his work.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Lake Keitele (detail, 1905)

Wonderful reflectionWith the biography of a few sentences in the previous paragraph, I obviously do Gallen-Kallela short, and that also applies to what I tell about his work in this article. His oeuvre is so extensive and diverse – in terms of subject and place of origin as well as in style and technique – that I can only discuss a fraction in this piece. My starting point with that is the wonderful reflection on the water, caused by the wind, which gives Lake Keitele not only abstract features, but also a lot of spaciousness, and evokes the atmosphere of being outside, on or near the water, where a cool breeze carries along the smell of the trees.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Aino Myth (detail of the triptych, 1891)

Aino MythThe oldest work by Gallen-Kallela on which this reflection struck me is the middle part of the triptych Aino Myth, which he painted in 1891. In 1888-1889 Gallen-Kallela made the first version of this triptych about an episode from the Finnish heroic epic the Kalevala, but on that version there's no reflection. In the version from 1891 it is there and the reflection contributes to the more dreamy atmosphere of this version, for which his fresh wife Mary Slöör was the model. In terms of composition, the reflection may not be the best addition here: due to the greater emphasis on the landscape, the attention is somewhat distracted from the story of Aino and Väinämöinen.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Lake View (1901)

More lakesSubsequently, such a reflection can be seen on landscape paintings a number of times, such as Lake View from 1901, which I think is also a beautiful painting. Unlike on Lake Keitele, Gallen-Kallela sticks to one stripe of reflection, which applies to more of his landscapes. Yet that one stripe is enough to suggest a lot of space, especially as a diagonal that tapers slightly in the distance, as in Lake View. On The Sauna Girl from 1904 as well, only one stripe of reflection can be seen, this time as an underline of the horizon to which it runs parallel. The background, with the lake and the wooded island, suggests that the location is the same as where Lake Keitele was painted. Gallen-Kallela clearly liked that place – and who can blame him? – which he also painted several times as an independent subject, including on this version with a rowing boat, from 1919.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: The Sauna Girl (1904)

In 1909, so five years after painting Lake Keitele, Gallen-Kallela painted Väinämöinen’s Boat Journey as part of the Kalevala paintings. On it, for the first time, the reflection can also be seen in a zigzag pattern, just like on Lake Keitele, but instead of a leading role, the lake here only plays the modest role of background. The light-dark contrast in the reflections in the water is (perhaps for that reason) also much lower than on Lake Keitele. You can judge for yourself whether you think Gallen-Kallela was right to do so; I am still in doubt.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Väinämöinen’s Boat Journey (1909), with an edited version below with a detail of Lake Keitele as background

The real dealWhen I unsuspectingly walked through the National Gallery in London in August 2019, I suddenly saw Lake Keitele. The canvas was slightly larger than I expected (53 x 66 cm) and above all less "smooth" than I thought based on photos on Instagram. That's of course also one of the main reasons to look at visual work in real life: the format, the use of color, the touch and more of such very determining things you do not see well in a photo. With the detailed photos above and below I try to give a bit of an impression nonetheless (with which you should take into account that a small shadow from the frame falls over the clouds). Gallen-Kallela painted especially the clouds quite thick, while you would expect that pasty use of paint in the foreground rather than in the background of a painting. The paint has been applied quite thinly from the trees in the background down to the center of the painting; there you can clearly see the texture of the canvas through the paint. In the hatchings below you can again clearly see the brushstroke, but the paint is still applied less thickly than with the clouds. You don't see all that very well in photos. So if it's allowed again: just watch it for real!

Akseli Gallen-Kallela: Lake Keitele (detail, 1905)

REPRESENTED FEELINGS

Louise Bourgeois: The Welcoming Hands

SWEDISH 'SUGGESTIVISM'

Anders Zorn: Omnibus